Why is Garamond the least legible? Because it’s smaller. These fonts are nominally all the same size. Only the line which the letters will be printed on will be 12-points tall. There is no guarantee that when you print out a font at 12-points that the letters will be 12-points tall. Rationally, then, it seems obvious that a 12-point font should be 1/6th of an inch tall, when printed. This is true in both physical and digital printing. The cost savings of switching to Garamond is largely imaginary.įonts are traditionally measured in a system called points, with one point corresponding to 1/72nd of an inch. Type expert Thomas Phinney has a great post explaining why, but we’ll do our best to present it in more layman-friendly terms here. Mirchandani is only 14, so he can be excused for not understanding this weirdo oddity of the way fonts are measured, but the biggest issue with his argument is that he measured Garamond at the wrong size! Therefore, the ink cost savings of switching to Garamond is largely imaginary. Which is, one imagines, what a government would like.At The Same Size, Garamond Doesn’t Actually Use Less Ink Than The Other Fonts Plus, New York Times writer Errol Morris and Cornell university psychologist David Dunning suggest texts in some fonts (the informal, oft-mocked Comic Sans, for example) tend to be viewed as not worth taking seriously, while other, weightier typefaces – particularly Baskerville – seem to inspire a belief that they are true. A 2010 Princeton university study found readers consistently retained more information from material displayed in so-called disfluent or ugly fonts ( Monotype Corsiva, Haettenschweiler) than in simple, more readable fonts ( Helvetica, Arial). Also, a 2010 study by the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay estimated it could save $10,000 a year by switching from Arial to Century Gothic, which uses 30% less ink – but also found that because the latter is wider, some documents that fitted on a single page in Arial would now run to two, and so use more paper.įont choice can affect more than just the bottom line. On that basis, he extrapolated, the federal and state governments could economise $370m (£222m) between them.īut should they? For starters, as the government politely pointed out, the real savings these days are in stopping printing altogether.

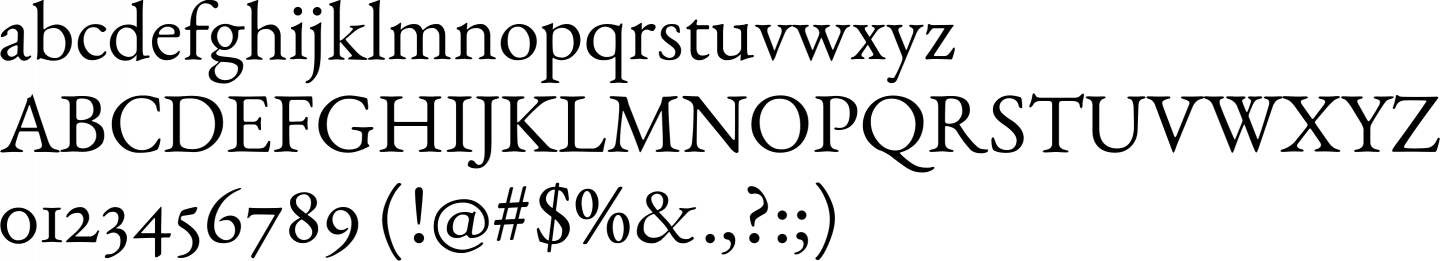

He discovered that by switching to Garamond, whose thin, elegant strokes were designed by the 16th-century French publisher in the 16th century by Claude Garamond, his school district could reduce its ink consumption by 24%, saving as much as $21,000 annually.

Shocked by the number of teacher's handouts he was getting at his new school, 14-year-old Suvir Mirchandani – having established that ink represents up to 60% of the cost of a printed page and is, ounce for ounce, twice as expensive as Chanel No 5 – embarked on a cost-benefit analysis of a range of different typefaces, CNN reports.

I n what can only be described as an impressive piece of research, a Pittsburgh schoolboy has calculated that the US state and federal governments could save getting on for $400m (£240m) a year by changing the typeface they use for printed documents.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)